What constitutes expressive musical performance? Is it simply playing “with feeling” due to some mysterious “essence” called musicality that only some lucky few are born with, as many believe? And is it therefore purely subjective, not open to objective evaluation about which there might be consensus?

Contrary to popular notions, there is actually a great deal of agreement among professionals about what constitutes expressive musical performance. There is even more agreement about what does not qualify as expressive musical performance. Differences of opinion mostly relate to details of application, not to underlying principles. Understanding of the principles -- the “deep structure of performance”, if you like -- is a matter of training, understanding and experience. Applications of the principles -- let’s call it “the surface structure” -- allows for more personal preferences.

In this essay I will present a conceptual framework for thinking about expressive musical performance. I will draw distinctions between principles, variable means of application, and a criterion for success. I will also present a framework for thinking about levels of complexity in performance.

Levels of abstraction

Expressive musical performance is underpinned by fundamental principles that allow for variable application. When the distinction between principle and application is missed, i.e. when levels of abstraction are confused, disagreements tend to degenerate into battles over “right” and “wrong”.

There may be different preferences for details of application, while the same fundamental principles are followed. In fact, it could be argued that it is the very nature of the principles of expressive musicality that allow for variety in application. Thankfully so, because the uniformity of “one right way” could be the death of musical expressivity. Context and individuality require a multiplicity of possible application for music to remain potent.

Let’s start with the greatest agreement: that which is unmusical. It is quite obvious when performance lacks expressivity. If we eliminate what is universally considered as “unmusical” or unexpressive, we can explore what remains as expressive, or “musical” performance.

What is generally regarded as unmusical? Unmusical is uniformity, rigidity, monotony, stasis. What would be the opposites? Variety, flexibility, contrast, movement. In other words, differences that convey information, as opposed to uniformity that doesn’t.

If the score is followed exactly, as far as it is possible to do so, the result is unexpressive. The typical notation app’s auditory electronic rendition of a score is a good example. It follows the score absolutely strictly. The result is rigidly metrical with no deviations, and therefore sounds mechanical. Humans experience it as totally unexpressive. At the very least there is no variation in time (no tempo fluctuations and no flexibility in rhythm), nor in timbre, nor in sound volume within phrases. So, per definition, the absence of deviation from the exact metrical structure of the score is unexpressive.

Musical or expressive performance is in fact deliberate deviation, according to specific principles, and within limits, from the rigid framework imposed by the notation system.

Music notation

Musical interpretation too often seems to put the cart in front of the horse, as if the notation system is the genesis for musical invention, rather than merely the medium for transmission. It is as if the notation system functions as a mold into which notes are poured in order to shape them into music. But perhaps that is the wrong way around. Musical invention/creativity comes first, after which it is codified (“arranged according to a plan or system”) using a notation system. It is as if the music is inevitably more or less distorted to make it fit the mold.

Notation comes after the fact; it is not the musical fact itself. The peasant spontaneously expressing his/her emotions in song doesn’t do so in the first place with our western notation system in mind. The expression does not confine itself to the restraints imposed by the notation system. The notation system might be used after the fact to codify the musical expression, but it is not the source.

The score -- the symbols arranged according to a strict metrical system -- is a representation of the music. It is not the music itself. It represents what the composer had in mind. But all forms of representation, of all subjects in any medium, inevitably involve deletion, distortion, and generalization. Therefore, the map is not the territory. The score is not the music.

The rigidity of organization imposed by the notation system, for all its great advantages, is at times contrary to the natural punctuation, and the ebb and flow of spontaneous musical phrasing. Consider the idea of note-groupings. The way notes are arranged by our notation system into groups within bars according to strict metrical divisions, is often contrary to natural or musical note grouping. Think of groups of notes as musical letters, words or sentences (phrases). Musical phrases often transcend the bar lines. So, for example, the first note in a bar is often actually the last note of a previous note grouping (or phrase), rather than the first note of a new group or phrase. This has definite consequences for musical phrasing (how we punctuate the music) in performance. For example, contrary to what most of us were taught, the first beat is not always the “strong” beat, with the up-beat to it the “weak” beat. If the first note in a bar is in fact the last note of a phrase, then it is "weak", not strong as the "norm" would have it for first beats in bars.

Principles of expressive performance

What might be principles of musical expressivity that allow for meaningful and variable deviation from the rigidities of the notation? These might be candidates:

How do we know that these principles are fundamental to musical expressivity? Partly, because they are spontaneously expressed in discourses about our musical experiences. Our words reflect them. And partly because performances that move us profoundly seem to consistently embody these principles.

Words reflect the cognitive metaphors we use to think about our experiences. In the case of music, these metaphors seem most prevalent:

Music is movement (movement, arrival points, pacing, tempo, momentum, flow)

Music is drama (character/s, events, moods, emotions)

Music is architecture (structure, shape)

Music is sex (male and female voices, tensions/resolutions, climaxes)

Music is nature

Music is painting (colour, line)

Music is argument

Our words about our musical experiences, whether as listeners or as performers, most often seem to indicate representations of movement, but also of unfolding drama, complete with characters and events. Indeed, we describe different musical ideas in terms of character, and the transformations and developments of those ideas in terms of events, usually leading to some kind of culmination point or climax, followed by resolution or conclusion.

Yet another attractive metaphor for thinking about music is philosopher Roger Scruton’s idea that effective music “makes an argument”. It argues, as it were, for the value of its musical ideas and their interplay and development to the point where a complete and convincing case has been laid out. As premises are laid out in philosophical discourse, and worked into a coherent argument, so musical ideas are set out and worked into a coherent and convincing musical narrative. If it is done skilfully, and if it conveys meaning over and above the mere machinations of technique and showmanship, we find it expressive. If it expresses more than craft, it "moves" us, that is, engages our emotions, and we then call it art.

In any case, music unfolds in time and we find it satisfying when it is an interesting journey, or engaging drama, or convincing argument, or whatever cognitive metaphor we use to understand its meaning.

Variable application

The principles for conveying musical meaning in performance, at least in Western art music, are fixed, but the means are variable. There is more than one way to convey a character, or tension and resolution, or foreground/background contrast, or balance of opposites, or movement, or punctuation. One might speed up where the other slows down; or play louder where the other goes softer; or take more time where another takes less time; or change timbre in a different spot, or articulate differently. But both are attempting to apply the same principles of musical expressivity.

Here is a simple example of variable application: there are two ways to convey a musical climax. One is to speed up toward the climax, and then slow down on the other side. The other is the opposite: to slow down toward the climax, and speed up as soon as it is reached, in both cases combined with supporting changes in loudness. The effect could be the same, following the principle of conveying tensions and resolutions in the music, but the application is different.

Application of the principles of expressive performance happens within a sophisticated frame of reference, which includes knowledge of music theory, composition, history, style, criticism, and acute awareness of performance practices past and present. These set the constraints to obey or to expand occasionally, as the case may be. The greatest players, having shown their mastery within the constraints, tend to venture beyond it eventually, expanding the framework within which the next generation of performers have to prove themselves. In such a way there is both continuity and change (dare we say "progress"?).

Criterion for application

What would be the most fundamental (or highest) criterion for the effective application of such principles? I would argue for proportionality. The proportions of all the elements of music and performance determine its expressive power. In other words, it is the proportionality of the performer’s application of the elements of music that determines the expressive success of the principles followed. It is the proportions that determine whether the conveyance of character, tensions/resolutions, movement, foreground/background, balance of opposites, and punctuation is convincing. What are such elements? Durations (including tempo and rhythm), dynamics, timbre, articulation, and punctuation (including silences).

Getting the proportions “right” certainly does not mean not that there is one, and only one, ratio and scale of proportions for any given piece, to be applied equally by everyone. Getting the proportions right means that within the “channel of style” (Dorothy DeLay’s term) set by convention (but subject to changes over time), each performer applies a coherent and consistent set of proportions. It is the coherence and consistency of proportion, more than specific proportions themselves that is crucial. The specifics may differ between performers, or even performances by the same performer, and from one era or convention to another. Certainly, there are scale differences between styles of music (greater in Romantic music than in Baroque music, for example). That is a given.

Individual preferences might differ, while still following the same principles. We might not like a given application of the principles, but that does not necessarily mean the principles are violated. In other words, it is not necessarily a question of right or wrong. Wrong would be when principles are violated, not when application is variable.

Variety is the spice of life, also in music. It allows for different performers at different times to perform the same music in varied ways that still conform to the same principles of musical expression.

It is akin to the use of natural language. The same finite rules of grammar allow for an infinite variety of expression. The rules for constructing well-formed sentences in any given language is followed by everyone, mostly intuitively. But no two people express themselves in the same way.

Levels of complexity

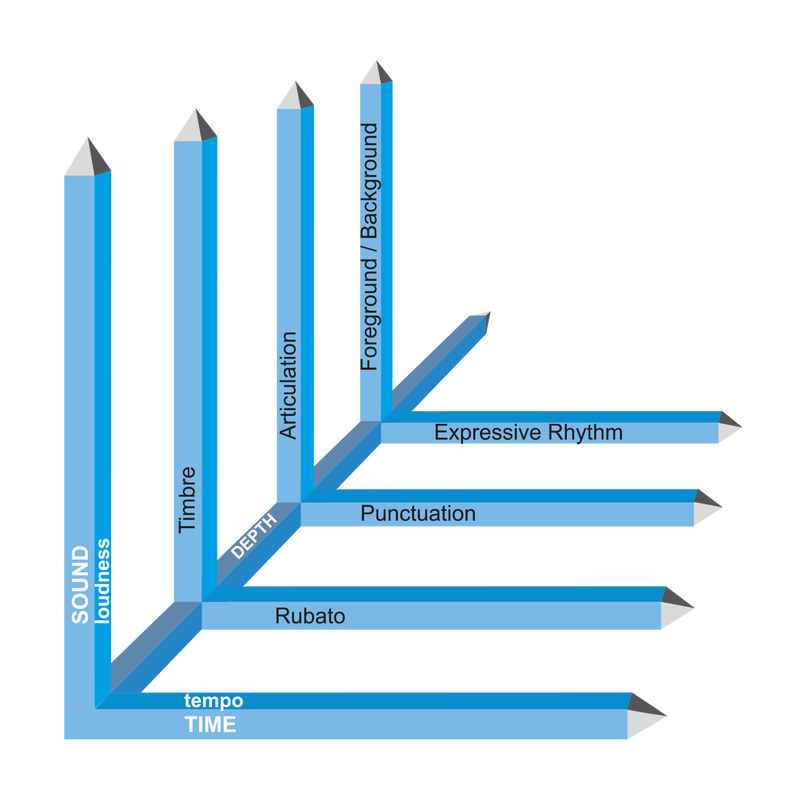

Of course, there are levels of complexity in music. Some music (and performance) could be called one-dimensional: tempo and dynamics basically remain the same throughout. Everything remains at one level. Muzak (“elevator music”) comes to mind. Other music has changes in tempo and dynamics. It gets louder and softer, and faster and slower. That would be two-dimensional music. At the top of the complexity hierarchy would be three-dimensional music and performance. That is when a third dimension is present. It could be called the depth-dimension. This third dimension involves the additional subtleties of timbre, articulation, foreground/background distinctions, along the Sound/Loudness axis; and rubato, punctuation and expressive rhythms along the Time/Tempo axis. See graph.

Usually the third dimension (the depth axis) is where greatness manifests. (The great violin pedagogue Dorothy DeLay cynically remarked that quite a few world famous soloists seem to get away with producing only good intonation and a big fat sound).

It should be added that the use and value of music is context dependent. There is a place for Muzak, and for party music, and for religious music, and for concert music. The subtleties of Brahms or Debussy would be utterly lost in an elevator, while Muzak would not suit a concert hall or cathedral. To each its own.

Summary

The summarize: expressive musical performance is not simply a subjective process of playing with feeling, but the application of principles of expressivity about which there is wide agreement among experts. These principles require systematic deviation from the rigours of the printed score, and allow for variable means of application resulting in differences in individual performances. The effectiveness of the applications of the principles depends on the proportions into which the elements of music and performance are arranged. The greatest mastery is characterized by fine distinctions in a third dimension of “depth” represented by a model of levels of complexity in music and performance. Such mastery requires thorough training, understanding and much mindful experience.

Contrary to popular notions, there is actually a great deal of agreement among professionals about what constitutes expressive musical performance. There is even more agreement about what does not qualify as expressive musical performance. Differences of opinion mostly relate to details of application, not to underlying principles. Understanding of the principles -- the “deep structure of performance”, if you like -- is a matter of training, understanding and experience. Applications of the principles -- let’s call it “the surface structure” -- allows for more personal preferences.

In this essay I will present a conceptual framework for thinking about expressive musical performance. I will draw distinctions between principles, variable means of application, and a criterion for success. I will also present a framework for thinking about levels of complexity in performance.

Levels of abstraction

Expressive musical performance is underpinned by fundamental principles that allow for variable application. When the distinction between principle and application is missed, i.e. when levels of abstraction are confused, disagreements tend to degenerate into battles over “right” and “wrong”.

There may be different preferences for details of application, while the same fundamental principles are followed. In fact, it could be argued that it is the very nature of the principles of expressive musicality that allow for variety in application. Thankfully so, because the uniformity of “one right way” could be the death of musical expressivity. Context and individuality require a multiplicity of possible application for music to remain potent.

Let’s start with the greatest agreement: that which is unmusical. It is quite obvious when performance lacks expressivity. If we eliminate what is universally considered as “unmusical” or unexpressive, we can explore what remains as expressive, or “musical” performance.

What is generally regarded as unmusical? Unmusical is uniformity, rigidity, monotony, stasis. What would be the opposites? Variety, flexibility, contrast, movement. In other words, differences that convey information, as opposed to uniformity that doesn’t.

If the score is followed exactly, as far as it is possible to do so, the result is unexpressive. The typical notation app’s auditory electronic rendition of a score is a good example. It follows the score absolutely strictly. The result is rigidly metrical with no deviations, and therefore sounds mechanical. Humans experience it as totally unexpressive. At the very least there is no variation in time (no tempo fluctuations and no flexibility in rhythm), nor in timbre, nor in sound volume within phrases. So, per definition, the absence of deviation from the exact metrical structure of the score is unexpressive.

Musical or expressive performance is in fact deliberate deviation, according to specific principles, and within limits, from the rigid framework imposed by the notation system.

Music notation

Musical interpretation too often seems to put the cart in front of the horse, as if the notation system is the genesis for musical invention, rather than merely the medium for transmission. It is as if the notation system functions as a mold into which notes are poured in order to shape them into music. But perhaps that is the wrong way around. Musical invention/creativity comes first, after which it is codified (“arranged according to a plan or system”) using a notation system. It is as if the music is inevitably more or less distorted to make it fit the mold.

Notation comes after the fact; it is not the musical fact itself. The peasant spontaneously expressing his/her emotions in song doesn’t do so in the first place with our western notation system in mind. The expression does not confine itself to the restraints imposed by the notation system. The notation system might be used after the fact to codify the musical expression, but it is not the source.

The score -- the symbols arranged according to a strict metrical system -- is a representation of the music. It is not the music itself. It represents what the composer had in mind. But all forms of representation, of all subjects in any medium, inevitably involve deletion, distortion, and generalization. Therefore, the map is not the territory. The score is not the music.

The rigidity of organization imposed by the notation system, for all its great advantages, is at times contrary to the natural punctuation, and the ebb and flow of spontaneous musical phrasing. Consider the idea of note-groupings. The way notes are arranged by our notation system into groups within bars according to strict metrical divisions, is often contrary to natural or musical note grouping. Think of groups of notes as musical letters, words or sentences (phrases). Musical phrases often transcend the bar lines. So, for example, the first note in a bar is often actually the last note of a previous note grouping (or phrase), rather than the first note of a new group or phrase. This has definite consequences for musical phrasing (how we punctuate the music) in performance. For example, contrary to what most of us were taught, the first beat is not always the “strong” beat, with the up-beat to it the “weak” beat. If the first note in a bar is in fact the last note of a phrase, then it is "weak", not strong as the "norm" would have it for first beats in bars.

Principles of expressive performance

What might be principles of musical expressivity that allow for meaningful and variable deviation from the rigidities of the notation? These might be candidates:

- character

- tension/resolution

- foreground/background

- kinetics (the ebb and flow of movement, momentum)

- balance of opposites

- punctuation (including the grouping of notes in musically meaningful ways that might transcend the groupings, often unmusical, imposed by the notation system).

How do we know that these principles are fundamental to musical expressivity? Partly, because they are spontaneously expressed in discourses about our musical experiences. Our words reflect them. And partly because performances that move us profoundly seem to consistently embody these principles.

Words reflect the cognitive metaphors we use to think about our experiences. In the case of music, these metaphors seem most prevalent:

Music is movement (movement, arrival points, pacing, tempo, momentum, flow)

Music is drama (character/s, events, moods, emotions)

Music is architecture (structure, shape)

Music is sex (male and female voices, tensions/resolutions, climaxes)

Music is nature

Music is painting (colour, line)

Music is argument

Our words about our musical experiences, whether as listeners or as performers, most often seem to indicate representations of movement, but also of unfolding drama, complete with characters and events. Indeed, we describe different musical ideas in terms of character, and the transformations and developments of those ideas in terms of events, usually leading to some kind of culmination point or climax, followed by resolution or conclusion.

Yet another attractive metaphor for thinking about music is philosopher Roger Scruton’s idea that effective music “makes an argument”. It argues, as it were, for the value of its musical ideas and their interplay and development to the point where a complete and convincing case has been laid out. As premises are laid out in philosophical discourse, and worked into a coherent argument, so musical ideas are set out and worked into a coherent and convincing musical narrative. If it is done skilfully, and if it conveys meaning over and above the mere machinations of technique and showmanship, we find it expressive. If it expresses more than craft, it "moves" us, that is, engages our emotions, and we then call it art.

In any case, music unfolds in time and we find it satisfying when it is an interesting journey, or engaging drama, or convincing argument, or whatever cognitive metaphor we use to understand its meaning.

Variable application

The principles for conveying musical meaning in performance, at least in Western art music, are fixed, but the means are variable. There is more than one way to convey a character, or tension and resolution, or foreground/background contrast, or balance of opposites, or movement, or punctuation. One might speed up where the other slows down; or play louder where the other goes softer; or take more time where another takes less time; or change timbre in a different spot, or articulate differently. But both are attempting to apply the same principles of musical expressivity.

Here is a simple example of variable application: there are two ways to convey a musical climax. One is to speed up toward the climax, and then slow down on the other side. The other is the opposite: to slow down toward the climax, and speed up as soon as it is reached, in both cases combined with supporting changes in loudness. The effect could be the same, following the principle of conveying tensions and resolutions in the music, but the application is different.

Application of the principles of expressive performance happens within a sophisticated frame of reference, which includes knowledge of music theory, composition, history, style, criticism, and acute awareness of performance practices past and present. These set the constraints to obey or to expand occasionally, as the case may be. The greatest players, having shown their mastery within the constraints, tend to venture beyond it eventually, expanding the framework within which the next generation of performers have to prove themselves. In such a way there is both continuity and change (dare we say "progress"?).

Criterion for application

What would be the most fundamental (or highest) criterion for the effective application of such principles? I would argue for proportionality. The proportions of all the elements of music and performance determine its expressive power. In other words, it is the proportionality of the performer’s application of the elements of music that determines the expressive success of the principles followed. It is the proportions that determine whether the conveyance of character, tensions/resolutions, movement, foreground/background, balance of opposites, and punctuation is convincing. What are such elements? Durations (including tempo and rhythm), dynamics, timbre, articulation, and punctuation (including silences).

Getting the proportions “right” certainly does not mean not that there is one, and only one, ratio and scale of proportions for any given piece, to be applied equally by everyone. Getting the proportions right means that within the “channel of style” (Dorothy DeLay’s term) set by convention (but subject to changes over time), each performer applies a coherent and consistent set of proportions. It is the coherence and consistency of proportion, more than specific proportions themselves that is crucial. The specifics may differ between performers, or even performances by the same performer, and from one era or convention to another. Certainly, there are scale differences between styles of music (greater in Romantic music than in Baroque music, for example). That is a given.

Individual preferences might differ, while still following the same principles. We might not like a given application of the principles, but that does not necessarily mean the principles are violated. In other words, it is not necessarily a question of right or wrong. Wrong would be when principles are violated, not when application is variable.

Variety is the spice of life, also in music. It allows for different performers at different times to perform the same music in varied ways that still conform to the same principles of musical expression.

It is akin to the use of natural language. The same finite rules of grammar allow for an infinite variety of expression. The rules for constructing well-formed sentences in any given language is followed by everyone, mostly intuitively. But no two people express themselves in the same way.

Levels of complexity

Of course, there are levels of complexity in music. Some music (and performance) could be called one-dimensional: tempo and dynamics basically remain the same throughout. Everything remains at one level. Muzak (“elevator music”) comes to mind. Other music has changes in tempo and dynamics. It gets louder and softer, and faster and slower. That would be two-dimensional music. At the top of the complexity hierarchy would be three-dimensional music and performance. That is when a third dimension is present. It could be called the depth-dimension. This third dimension involves the additional subtleties of timbre, articulation, foreground/background distinctions, along the Sound/Loudness axis; and rubato, punctuation and expressive rhythms along the Time/Tempo axis. See graph.

Usually the third dimension (the depth axis) is where greatness manifests. (The great violin pedagogue Dorothy DeLay cynically remarked that quite a few world famous soloists seem to get away with producing only good intonation and a big fat sound).

It should be added that the use and value of music is context dependent. There is a place for Muzak, and for party music, and for religious music, and for concert music. The subtleties of Brahms or Debussy would be utterly lost in an elevator, while Muzak would not suit a concert hall or cathedral. To each its own.

Summary

The summarize: expressive musical performance is not simply a subjective process of playing with feeling, but the application of principles of expressivity about which there is wide agreement among experts. These principles require systematic deviation from the rigours of the printed score, and allow for variable means of application resulting in differences in individual performances. The effectiveness of the applications of the principles depends on the proportions into which the elements of music and performance are arranged. The greatest mastery is characterized by fine distinctions in a third dimension of “depth” represented by a model of levels of complexity in music and performance. Such mastery requires thorough training, understanding and much mindful experience.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed