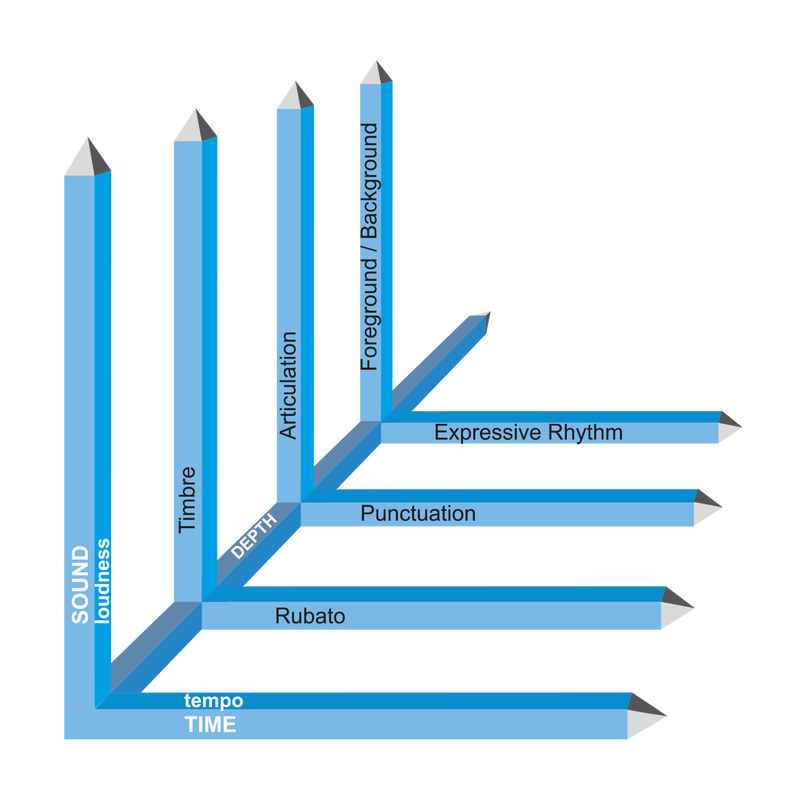

31/5/2020 Some more thoughts, for what they are worth. Some music (and performances) can be thought of as being ONE DIMENSIONAL. Basically, there is one level of loudness and one steady tempo throughout. Muzak (elevator music) comes to mind as an example. Some music is TWO DIMENSIONAL. There is variation in loudness (louder and softer), as well as in tempo (faster and slower). If we think of it on a graph, the vertical axis would be loudness, and the horizontal axis would be tempo. But then there is THREE DIMENSIONAL music/performance. The third dimension can be thought of as the depth dimension, represented by a third axis. The depth dimension involves subtle elements like rubato, timbre, articulation, punctuation, foreground/background, and expressive rhythm. It is the third dimension - the depth dimension - that we strive for in classical concert music. (graph copyright mine)

You'll notice that timbre, articulation and foreground/background are elements that add depth to the Sound/loudness axis, while rubato, punctuation and expressive rhythm add depth to the Time/tempo axis.

30/5/2020 Here are a few thoughts about principles.

Left hand accuracy: for me the operating principle for left-hand accuracy is LOGISTICS (“the detailed organization and implementation of a complex operation”), that is, understanding the placement of fingers IN RELATION to other fingers already placed and to be placed, on a grid that consists of the four strings and imaginary fret lines that lie diagonally across the strings. On this grid finger placements are reference markers for other finger placements. The basic elements are: spacing between fingers, the basic units being half-tone and whole tone spaces; patterns of such finger spacing; the fundamental FRAME of the hand, formed by two whole tone spacings plus one half-tone spacing between the fingers, forming a perfect fourth on one string and an octave on two adjacent strings with the first finger on the lower string and the fourth finger on the higher string.

With reference markers like these we employ strategies for movement between locations. Such strategies involve, at least,

keeping the fingers and other parts of the hand maximally in contact with the instrument as a rich frame of kinesthetic reference;

thinking of the normal Frame of the hand as a basic unit in itself (in addition to the fundamental units of half- and whole tone spacings between fingers);

using stepping stones and/or anchors/markers/reference points for navigating the fingerboard.

Planning backwards (using upcoming finger locations as reference points from which to plan backwards) as well as forwards (using fingers already placed as reference points for finger placements to follow), etc...

For sound production the operating principle is FRICTION control: how best to produce the friction required for a particular sound, using different proportions of weight, speed, sounding point and amount of hair in contact with the string.

For interpretation, the operating principle is PROPORTION. See my article, “Reverse Engineering Musical Performance”.

Fundamental principle of technique: BALANCE

- balanced use of flexor and extensor muscles

- balanced stance (feet hip-width apart; head balanced and facing forward; all joints loose; distance equal either side of vertical midline.)

- balanced bow grip:

1. Thumb next to the frog and on the thumb-grip.

2. Other fingers equally spaced and placed on the bow so that the thumb is approximately in the middle of the hand.

3. Fingers rounded.

4. Knuckles flat(ish)

5. Hand, wrist and forearm straight in-line.

6. Bow & arm forming a "square" on the level of the string when in the middle of the bow on the string.

[05/28, 18:49] It is a truism that there are many different ways to play the violin very well, and also that there are many different ways of THINKING about violin playing. Here is an example. Hadelich maintains that spiccato is primarily a wrist action, although in his part 2 of his "spiccato tips", he does say that sometimes he uses his arm for a particular kind of spiccato. DeLay, on the other hand, regarded spiccato as primarily an arm action, swinging from the shoulder, with the wrist and fingers following the movement. In both cases the thinking has led to excellent results. Hadelich has incredible spiccato skills. So does many famous violinists who followed DeLay's way of thinking. I tend to think that it is not really about who is right and who is wrong, but whether or not the way of thinking about an action is useful for the person involved. Different ways of thinking can lead to the same results. Notice that Hadelich's spiccato tends to be higher up on the bow, unless he needs it slow and loud. Many other violinists, using more arm motion than Hadelich, tend to play spiccato slightly lower on the bow. They all play fantastically, even though they came to their results by different ways of thinking. Perhaps one can think of such different ways of thinking about highly complex actions as "metaphors" that help the nervous system to learn movements that are too complex for complete and "correct" conscious analysis. Just a thought...

You'll notice that timbre, articulation and foreground/background are elements that add depth to the Sound/loudness axis, while rubato, punctuation and expressive rhythm add depth to the Time/tempo axis.

30/5/2020 Here are a few thoughts about principles.

Left hand accuracy: for me the operating principle for left-hand accuracy is LOGISTICS (“the detailed organization and implementation of a complex operation”), that is, understanding the placement of fingers IN RELATION to other fingers already placed and to be placed, on a grid that consists of the four strings and imaginary fret lines that lie diagonally across the strings. On this grid finger placements are reference markers for other finger placements. The basic elements are: spacing between fingers, the basic units being half-tone and whole tone spaces; patterns of such finger spacing; the fundamental FRAME of the hand, formed by two whole tone spacings plus one half-tone spacing between the fingers, forming a perfect fourth on one string and an octave on two adjacent strings with the first finger on the lower string and the fourth finger on the higher string.

With reference markers like these we employ strategies for movement between locations. Such strategies involve, at least,

keeping the fingers and other parts of the hand maximally in contact with the instrument as a rich frame of kinesthetic reference;

thinking of the normal Frame of the hand as a basic unit in itself (in addition to the fundamental units of half- and whole tone spacings between fingers);

using stepping stones and/or anchors/markers/reference points for navigating the fingerboard.

Planning backwards (using upcoming finger locations as reference points from which to plan backwards) as well as forwards (using fingers already placed as reference points for finger placements to follow), etc...

For sound production the operating principle is FRICTION control: how best to produce the friction required for a particular sound, using different proportions of weight, speed, sounding point and amount of hair in contact with the string.

For interpretation, the operating principle is PROPORTION. See my article, “Reverse Engineering Musical Performance”.

Fundamental principle of technique: BALANCE

- balanced use of flexor and extensor muscles

- balanced stance (feet hip-width apart; head balanced and facing forward; all joints loose; distance equal either side of vertical midline.)

- balanced bow grip:

1. Thumb next to the frog and on the thumb-grip.

2. Other fingers equally spaced and placed on the bow so that the thumb is approximately in the middle of the hand.

3. Fingers rounded.

4. Knuckles flat(ish)

5. Hand, wrist and forearm straight in-line.

6. Bow & arm forming a "square" on the level of the string when in the middle of the bow on the string.

[05/28, 18:49] It is a truism that there are many different ways to play the violin very well, and also that there are many different ways of THINKING about violin playing. Here is an example. Hadelich maintains that spiccato is primarily a wrist action, although in his part 2 of his "spiccato tips", he does say that sometimes he uses his arm for a particular kind of spiccato. DeLay, on the other hand, regarded spiccato as primarily an arm action, swinging from the shoulder, with the wrist and fingers following the movement. In both cases the thinking has led to excellent results. Hadelich has incredible spiccato skills. So does many famous violinists who followed DeLay's way of thinking. I tend to think that it is not really about who is right and who is wrong, but whether or not the way of thinking about an action is useful for the person involved. Different ways of thinking can lead to the same results. Notice that Hadelich's spiccato tends to be higher up on the bow, unless he needs it slow and loud. Many other violinists, using more arm motion than Hadelich, tend to play spiccato slightly lower on the bow. They all play fantastically, even though they came to their results by different ways of thinking. Perhaps one can think of such different ways of thinking about highly complex actions as "metaphors" that help the nervous system to learn movements that are too complex for complete and "correct" conscious analysis. Just a thought...

RSS Feed

RSS Feed